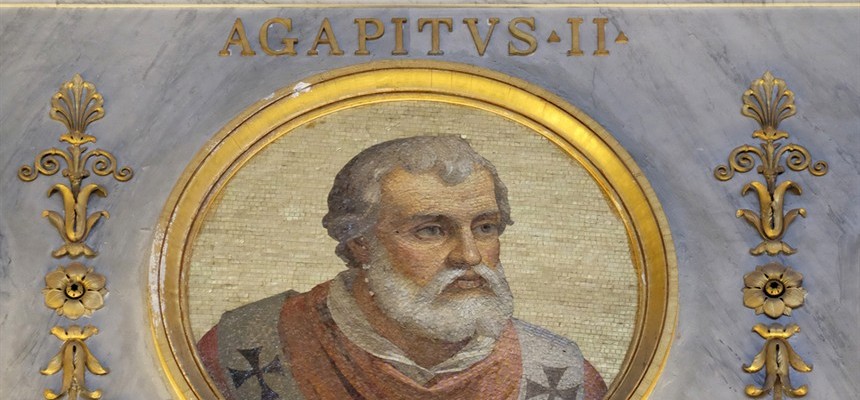

Born around 905, Agapetus was one of the longest reigning popes, ruling nine and one-half years. Son of a Roman father and a Greek mother, he lived his life mostly in Rome. By the time he was forty, he had become cardinal deacon. At some point, he attracted the attention of the current Roman dictator, Alberic II, who completely controlled the independent city-state of Rome.

When Pope Marinus II died, Agapetus was nominated for the now-empty seat of Peter by Alberic. On May 10, 946, Agapetus was elected pope. This election put Agapetus in a peculiar position. As pope, Agapetus should have been controlling the religious and political aspects of the Papal States. Alberic ruled so tightly, that all Agapetus was able to do was attempt to wrest a modicum of ecclesiastical discipline from the churches and cloisters which had become decadent.

Agapetus was a wise and pious administrator and this is where he shined. The major players in this scenario were King Otto of Germany, King Louis IV of France, Berengar II and Hugh of Arles, who both claimed to be king of Italy. Italy was constantly in chaos due to the two Italian claimants and their constantly shifting allies. Hugh died in 947, leaving Berengar to fight.

Monasteries in Italy and Germany had been deprived of their lands and buildings as dukes and counts laughed at the rights of the Church. Agapetus pushed to reestablish the monasteries’ holdings, especially in Beneventum and Capua, Italy. In Germany, the pope granted sweeping control of the Church to Otto of Germany in exchange for sending priests and bishops, consecrated by the king rather than the pope, to Denmark. In that pagan country, and, soon, other Scandinavian countries, the Good News was spread for the first time. King Otto and Pope Agapetus became good friends over this.

Rival claimants of the bishopric of Reims fought in two synods before who was the real bishop was sorted out.

By 951, the chaos in Italy had become of such concern to the rule of Rome, Alberic, that he asked Agapetus to use his power of persuasion to get Otto to cross the Alps and help out the Italians. Otto did arrive, but late, having to squelch a rebellion begun by his own son. Yet, when Otto’s personal negotiators arrived ahead of him, Alberic would not receive them. In an unstable agreement, Berengar became Otto’s vassal in 952. But it did not last long.

Within a few years, Berengar’s troops attacked the Papal States, and Rome, itself, right around the time that Alberic was dying. Fearful of his legacy, Alberic forced the pope and the nobles of Rome to guarantee their support of Octavian, Alberic’s son, as the next pope. The problem was that Octavian was not much of a Christian and was only 18.

Agapetus died soon after Alberic, in the late fall of 955. He died at the relatively young age of 50. Pope Agapetus was buried in the Lateran basilica near the tombs of Popes Leo V and Paschall II. And Octavian came to sit on the Chair of Peter.

Recent Comments